“Holy Titanic, fatbergs dead ahead!”

We’re all familiar with the concept of an iceberg; a large, floating mass of ice that glides innocently along on the current doing no harm. No harm, that is, until it comes up against theWhite Star Line’s“unsinkable” new passenger ship, The Titanic, which two hours and 40 minutes later finds itself laying on the floor of the Atlantic.

We learned our lessons about icebergs from that disaster, but as we approach 2020 a new type of ‘berg’ looms on the horizon, and threatens to do even greater damage by way of clogging sewers, ruining waste water infrastructure and shutting down sewage treatment facilities in congested cities .

WHAT ARE FATBERGS?

Known as fatbergs, these enormous, slimy, floating masses are made up of fats, oils and non-biodegradable items that have been incorrectly disposed of in sewer systems. These wayward items join together into putrid, solid masses bound together by the fats and oils, which have also been carelessly washed down the pipes via kitchen sinks and drains.

When cooking oil enters the kitchen drain it travels through your pipes to the local sewer, where it mixes with other waste water, chemicals and substances, including calcium. The oils and fats break down into their component parts of glycerol and fatty acids, which bind with the calcium to create a compound with a soapy consistency. This ‘soap’ remains in the sewer system and when water levels rise (such as during storms or heavy rains) the fatty blobs cling to the ceilings and sides of the pipes, building up and becoming waxy fatbergs.

By allowing oils and fats to enter waste treatment systems through kitchen sinks and drains and by placing non-biodegradable products into toilets and sewer pipes, fatbergs of up to 70 metres in length are being formed and are moving through our waste pipes in increasing numbers.

WHY ARE SO MANY FATBERGS BEGINNING TO FORM?

Research into the factors leading to the creation of fatbergs revealed:

- one in four people admit they routinely pour cooking oils down the drain

- 50 per cent of people admit they wash leftover sauces and/or dips down the kitchen sink

- 14 per cent of people scrape food into their sink’s drainage pipes.1

As populations and the range of commodities available for consumption increase across the globe, greater numbers of items (such as nappies, personal hygiene products, condoms, paper towels and dental floss) are also being disposed of incorrectly down drains and pipes that are designed to only carry fresh, storm and waste water or sewage.

The problem is significant and widely acknowledged in the United Kingdom, however it is now being identified as a major issue that is negatively impacting the local environment and waste water treatment infrastructure in most developed regions of the world.

ARE FATBERGS A PROBLEM IN AUSTRALIA AND NEW ZEALAND?

In January this year, the ABC spoke about the issue of fatbergs with Queensland Urban Utilities (QUU) which manages water and waste services for five local council areas, including Brisbane City.

They found that about one in ten sewer pipe blockages and 250 sewage overflows were caused by fatbergs each year, and that clearing them cost about $1.2 million.

And if your reaction to that is “¦ “well that’s notmymoney” think again about who’s paying your water bills.

QUU spokesperson, Sarah Owens, said the largest fatberg they’d found was under Campbell Street in the Brisbane suburb of Bowen Hills. At seven metres in length and 60 centimetres wide it was a baby compared to some of the monsters London authorities are dealing with, but unless current pipe and drain practices are addressed, who knows what the future will bring.

Watercare (New Zealand) is also grappling with problems associated with an increasing number of fatbergs one of which led to a sink hole opening up in Dannervirke on the North Island.

The fatberg had blocked the main sewer, and that, combined with the army of rats that were feeding on it, caused a sewer pipe failure which then led to the sinkhole.

Peter Rogers, Watercare’s manager for asset protection, said they were having a constant battle to keep fatbergs under control.

“It’s a big problem,” he said when interviewed on the Morning Show by Mark Sainsbury.

“They block our pumps, so our pumps stop and that can lead to overflows in our network.

“We have to deploy teams to jet out a lot of the fat, which ultimately hits the taxpayer in the pocket.”

AND ON THE ISSUE OF ‘FLUSHABLE’ WIPES?

“We’ve not found one [wet wipe] that breaks down like common toilet paper,” he said.

“I mean, physically, yes you can flush them down the toilet, but it causes big problems.

“It’s a big cost to home owners when they get blockages in their private line, and it’s a big cost for us which again, is really the ratepayer that’s paying for it.”

When are fatbergs most likely to form?

There are two times of the year during which fatbergs start popping up everywhere.

CHRISTMAS

Perhaps it’s the extra fats and grease from the roast pork, maybe there are more tourists and holidaymakers using sinks, drains, pipes and toilets that aren’t their own or could it be that we’re all just that little bit lazier and time-poor at that time of year? Whatever the reason, the Christmas festive season seems to encourage fatberg formation and a blocked sewer pipe is the perfect way to ruin Christmas.

WINTER

The other fatberg boom time is winter, when the chill in those damp, dark pipes is greatest and fats solidify more quickly. Fats and oils are the essential bond that keeps the fatberg together, so the more quickly it solidifies, the more biodegradable products it can trap within its slimy outer casing, and the larger the fatberg becomes.

What can you do?

IN THE KITCHEN

To try to ensure households do not have to bear the financial cost, inconvenience and potential health issues associated with clogged or blocked kitchen drains and sewer pipes as a result of fatbergs, QUU is urging people to ‘Think at the Sink’and make sure fats, oils and food scraps are put in the bin; not down the sink.

NEVER put the following down your kitchen drainage pipes (sink):

- fat – wait for left over fat to cool in the pan and scrape it into a bin

- grease – wipe grease from pans/plates with paper towel and place in bin

- oil – pour used oil into a container and either refrigerate it or bin it

- chemical – never flush harsh chemicals such as paint down the drain

- tea leaves, coffee grounds or food scraps.

IN THE BATHROOM

And in a similar vein, UK-based water authority, South West Water (SWW) is urging people to remember the three Ps when it comes to flushing.

“Only flush the three Ps,” said SWW treatment manager, Andrew Rowntree, “that is pee, paper and poo.”

Whether out of complacency, laziness or ignorance, many people are currently flushing a range of items down the toilet which will simply not break down.

NEVER flush the following down your sewer pipes (toilet):

- disposable nappies

- pads and tampons

- paper towels

- cosmetic wipes

- dental floss

- baby wipes

- cigarette butts.

NEVER put the following into bathroom or laundry sinks or shower drains:

- harsh cleaning chemicals or medicines

- hair

- oily beauty products

- dental floss

Not only is this important for your own household’s health, but for the health of our beautiful waterways and marine life as well.

You can also access an article on ways to keep your kitchen drains and pipes in good working order here (insert link to our Kitchen Pipe Health Article 1).

“BUT I BUYFLUSHABLEWIPES!”

Just because a brand of wipes islabeledas being flushable, don’t presume it will break down as easily or as quickly as toilet paper. Many products marketed as flushable take much longer to break down than paper, and a number of significant court actions have been launched recently by the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) over the issue.

In fact in its opening volley against consumer goods giant, Kimberley-Clarke Australia, the ACCC legal team said the company’s Kleenex ‘flushable’ wipes were an ‘environmental catastrophe’. Consumer advocate group, Choice, also lodged a complaint against reportedly flushable wipes after their investigation revealed that even after six hours in a cement mixer filled with water the wipes had not begun to break down. The complaint led to the Federal Court ordering Pental to pay penalties totalling $700,000, for making false and misleading representations about its White King ‘flushable’ toilet and bathroom cleaning wipes.

With Sydney Water having removed more than 1000 tonnes of wet wipes from sewer pipes in two years, and 65 per cent of sewer blockages being caused by wet wipes, Choice spokesperson, Tom Godfrey, said action had to be taken.

“Households, local councils and water services organisations are struggling with the cost of removing these wipes from the sewage system,” he said.

“Companies need to clean up their act.”

Part of the problem is a growing trend amongst young males to use ‘flushable’ wipes rather than toilet paper. According to sales data personal wet-wipe salesreached an estimated $2.2 billionin 2015 and sewage authorities believe the only way the trend will be reversed is through changes in legislation.

Ms Owens, from QUU agrees that ‘flushable’ wipes are a big problem in Australia’s sewer networks, adding that the issue is exacerbated by the absence of an enforceable standard to distinguish just how easily a wipe has to break down in order for it to be deemed ‘flushable’.

“They wreak havoc at our pump stations and treatment plants,” she said.

“They can also cause blockages in household drains and pipes and leave home owners with a hefty plumbing bill.”

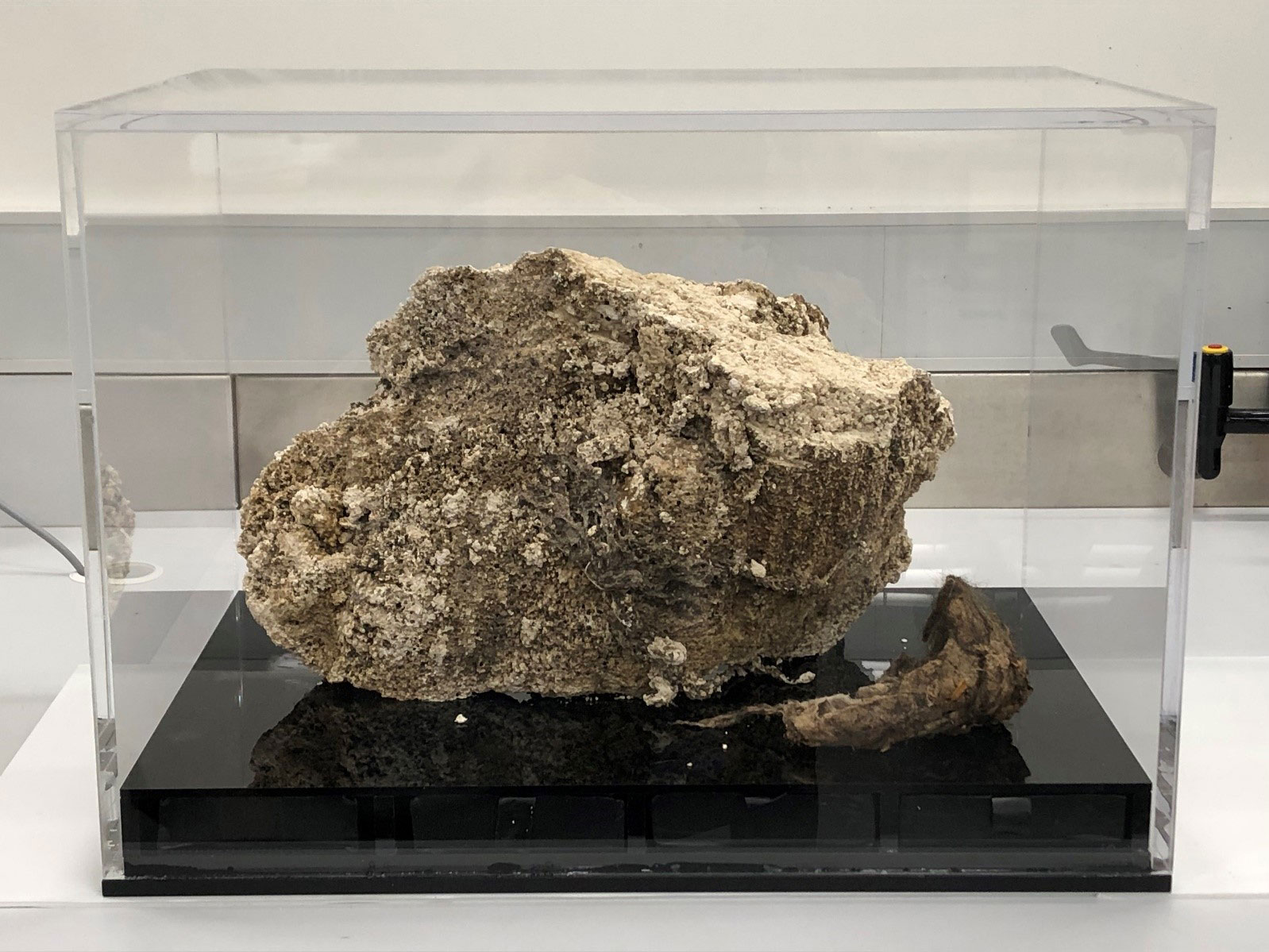

REMOVING FATBERGS AND OTHER USES

Breaking the fatbergs up is no easy task either. In 2015 a 10-tonne lump cost close to $AUD750,000 to remove, and a 130-tonne, 250 metre monster found in Whitechapel, London, took workers in masks and protective clothing many weeks to break up using high-powered jet hoses, shovels, hand tools and jet rodding.

That fatberg, once broken up, was melted down and converted into biofuels which were then used to power London buses, however there are no such plans as yet for recycling the masses in Australia.

With so many people living in such close proximity in London, and intricate networks of aging sewer infrastructure, the problems are currently much worse there than in Australia and New Zealand. However fatbergs are becoming increasingly prevalent and regular occurrences in our water treatment facilities and are causing significant unnecessary expenditure, which only education and more responsible use of household pipes can address.

_______________________

Sources:

- Queensland Urban Utilities

- The Australian Broadcasting Commission (2019):accessed June 10.

- Australian Competition and Consumer Commission website: accessed June 10.

All images courtesy ofYarra Valley Water.